TERRACOTTA POMEGRANATE WITH TRACES OF PAINT

nothing except what survives the ancients.

yours and mine alike. take the terra-

cotta pomegranate with traces of paint,

for instance. greek, 4th or 5th century

before christ. the precise shape and size

of its model, faded to the unbaked bread

color common to that region’s cooked earth

remnants. one tip in its persistent calyx

crown still flecked with pigment: weathered

hints of pinkish-red as evidence: it looked

just like this once. like you could eat it. like you

would hold the whole of its firm fauxness

in both hands and think that lacquer skin

could crack into the true fruit’s garnet beads

within. one story goes, each contains seeds

totaling in number torah’s commandments,

though that myth’s as easy to disprove

as it is to lose count trying. I know hebrew

only by phonetics––can pronounce with passing

accent reading right-to-left and have no clue

what I’m saying. I picked it up almost

by accident, a decade after I’d missed

my chance to become bar mitzvah,

which translates to, adulting, in a sense

too-perfect to overstress. my arabic

consists of, forget — one sour instructive

for that family branch’s disconnect.

through millennia, the root word, רימון / رمان

remains twinned along the stem of each language

grown out of the levant, to mean both “fruit

with many seeds,” and “hand grenade.” pome•

granate. the old-french-derived-english

of our lingua franca echoes the two ideas if

you listen close and play semantics. a simple

way to summon spirits. in my new england

dialect, conditioned by ghosts still living

in my throat, root and route will never

homophone. as if one wrought itself out of the sonic

bones of its predecessor. shaped from her rib.

my history’s mixed up with the bigger world of gods

and trade, things borne across, as in the literal gloss

of “translation.” people moving through thought

and places promising home, nightmares

of nation-making, pales of settlement. tongues

tied in marriage knots. it took from the beginning

of time until that day by the famous museum

for me not to ask what are you staring at?

when the stranger fixed me in her glare

on the street in paris. like she was looking

at an exhibit. my face as foreign object.

I’d just come from seeing the clay pomegranate

crammed into an underlit corner of the louvre’s

sub-basement, where it had begged me to explode

the glass cast around its plinth and sunder

apart pith in a bowl filled with water. at least,

that’s how my mother’s mother taught her,

who told me before I knew a word which would

refuse to distinguish fruit from shrapnel. one

name for war, or, better yet, the best method

known to defuse its billion red grains, rendered

separate from the bitter whiteness of its flesh.

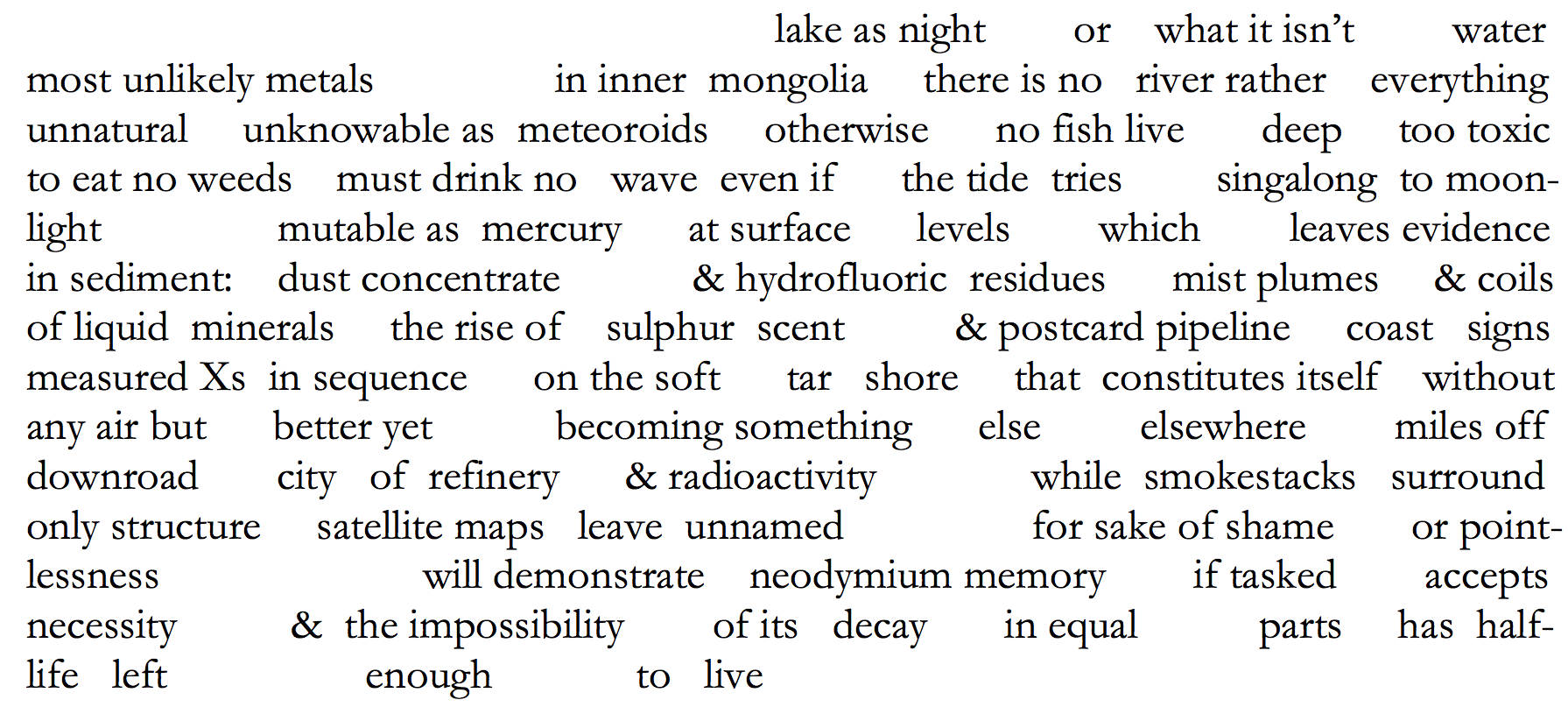

RARE EARTH

Baotou Lake, Baogang Steel and Rare Earth Complex, China

Daniel Barnum’s poems and essays appear in or are forthcoming from West Branch, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Massachusetts Review, The Offing, Pleiades, Muzzle, and elsewhere. A former fellow at the Bucknell Seminar for Younger Poets, they are a current Pushcart Prize and Best New Poets nominee. Their chapbook, Names for Animals, was selected as the winner of the Robin Becker Prize, and is available from Seven Kitchens Press. They live and write in Columbus, Ohio, where they serve as the associate managing editor of The Journal.